Many Americans are familiar with Social Security’s projected shortfall and the public debate on how to fix the program’s finances. Going forward, fewer workers will support a larger number of retiring baby boomers. Without some combination of tax increases and benefit cuts, Social Security’s operating deficit is expected to exceed $800 billion over the next 10 years.¹

Some of the nation’s public- and private-sector pension plans are facing similar financial challenges. Unlike defined-contribution plans such as 401(k)s, pensions are defined-benefit plans that promise to pay lifetime benefits to retirees based on length of service and their pre-retirement salaries.

Pension plans that become severely underfunded could eventually fail, leaving participants without the retirement incomes they were counting on, or transferring the burden to taxpayers if a government bailout is needed.

Here’s a closer look at how pensions operate and why more of these retirement plans may be under pressure.

Dealing with Deficits

Investment losses from the 2008 financial crisis reduced public pension assets, and some states chose not to make their full recommended contributions.² An estimated $800 billion in unfunded liabilities for public-employee pensions has been reported, with individual state funding levels ranging widely from 40% to 80%.³

A long period of low interest rates has taken a toll on private-sector pensions. The funding deficit of the 100 biggest corporate pension plans rose to $411.8 billion at the end of 2012, and the plans were 76.4% funded (on average). A funding ratio of 80% is usually considered healthy.4

Low rates affect the calculation of a plan’s funding ratio by increasing the value of future benefit obligations (or liabilities). Such liability losses have more than offset investment gains that exceeded expectations in three of the last four years.5 For individual companies, a loss of funding status typically results in a charge to their balance sheets at the end of the fiscal year and increases pension expenses the following year.

Repercussions for Retirees

To help reduce pension costs, 45 states have cut benefits for teachers, police, firefighters, and other public workers. Because most major changes affect only new workers, much of the savings won’t be realized for several decades. Twelve states, however, have reduced benefits for current retirees, including nine that suspended cost-of-living increases.6

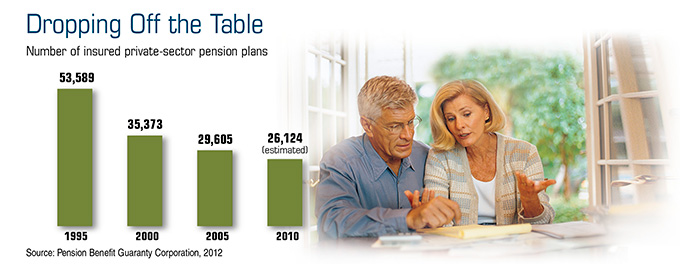

To help control costs, some corporations are closing pensions to new employees, freezing benefits for current workers, or terminating plans and offering lump-sum payments. Many companies are switching to defined-contribution plans in which the workers bear the investment risks.7

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) is a U.S. government agency that provides basic pension benefits for participants of failed private-sector plans. The PBGC is funded by insurance premiums and recovered assets, not tax dollars, but is itself operating under a growing deficit in recent years.

Because most private-sector (and some public-sector) pension benefits do not rise with inflation, a fixed benefit amount that seems adequate initially might cover a much smaller share of a retiree’s living expenses after 20 years.

Public and private pensions are operating in a difficult environment, and some plan sponsors may not be able to keep all the promises that were made to workers. Therefore, when assessing your own retirement income needs, it might be wise not to depend solely on a pension.

1, 3) TIME.com, September 26, 2012

2) Yahoo! Finance, October 18, 2012

4) FoxBusiness.com, January 18, 2013

5) Milliman, 2013

6) The Wall Street Journal, September 21, 2012

7) The New York Times, July 20, 2012