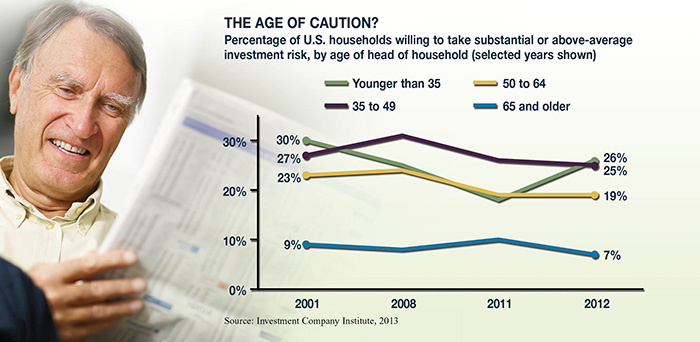

A recent academic study confirmed that willingness to take investment risk is affected not only by an investor’s age but by the current economic climate.1 The more conservative risk tolerance associated with age might be considered rational behavior, because older investors may have less time to recover from potential losses and generally need to tap their savings sooner than younger investors.

Changing one’s risk tolerance based on current economic conditions, however, may be less rational. Assuming more risk when the market is up and less risk when the market is down might encourage you to buy when prices are high and sell when prices are low.

Because no one can predict the market’s ups and downs, a wiser approach might be to adopt an investment strategy appropriate for your personal situation and to maintain it regardless of market volatility. Doing so could help you become a more rational investor.

Reference Points and Mental Accounts

The field of behavioral finance seeks to understand how and why investors react to different events and outcomes. It’s been widely accepted for some time that investors tend to react more negatively to losses than they react positively to gains. Recent research suggests that people have a subjective reference point for considering whether an investment is a success or a failure, and they may have different reference points for different investments. Investors also use mental accounts to organize investments for specific goals.2

Understanding your own reference points and mental accounts may help you determine an appropriate asset allocation based on your risk tolerance. Although asset allocation is a method to help manage investment risk, it does not guarantee against investment loss.

Hard-Wired Responses

Neuroscientists are discovering that many emotions and behaviors are “hard-wired” in the brain. In an experiment where investing was rewarded more highly than not investing, people with damage to areas of the brain related to emotions and risk — including the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and insula regions — were not constrained by investment losses and achieved higher returns than those with healthy brains. In other studies, however, people with damage to these areas have gone “bankrupt” due to poor judgment and taking on too much risk.3

Another experiment, which looked at how people use past rewards to predict future payoffs, found that most subjects were unduly influenced by the two most recent results, perceiving a pattern where there was none. However, people with damage to a region of the brain called the frontopolar cortex made decisions primarily on cumulative reward history rather than on the most recent outcomes.4

The brain may also have a “motivation center” that drives efforts to achieve a goal based on the perceived value of success. In a series of tests, an increase in the dollar value of a potential reward created increased activity in a region of the brain called the ventral striatum, which led to increased efforts to achieve the reward.5

These findings suggest that investors may have to control natural responses that could lead to their becoming too risk averse, reacting too quickly, or pursuing potential gains without appropriate caution. If you become overly emotional when it comes to your investments, it may help to take a step back and consider the situation rationally based on your overall financial strategy.

1) University of Missouri, 2012

2) AdvisorOne.com, February 23, 2012

3) Forbes.com, October 16, 2012

4) The Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2012

5) ScienceDaily.com, February 22, 2012